A day out on the

water

Roger Blench

Journeys with Kay in

At the end of December 2002,

I went down to

One of Kay’s long-term and

picturesque collaborators was Richard Freeman, who had worked with her since

the days of the Nigerian Civil War. Richard was a speaker of the Olodiama language, and a great source of knowledge about

the Delta. He produced a vast, rambling manuscript on the fisheries of the

Delta which we spent many years trying to publish. But he also a poet and short

story writer and someone for whom dreams were very

real. He would disappear for weeks at a time and once returned with a tale of

kidnap by cannibals. Kay was assisting him to build a house in his village,

though it later turned out that this structure was largely science fiction and

the hopeful photographs with which he reassured her were actually someone

else’s house in another place. Richard also had the most complex domestic

affairs and, through the agency of his multiple wives and others, contracted

AIDS and died in 2001. Richard’s village, Ikebiri,

was inaccessible, and Kay had always nurtured an ambition to see his grave.

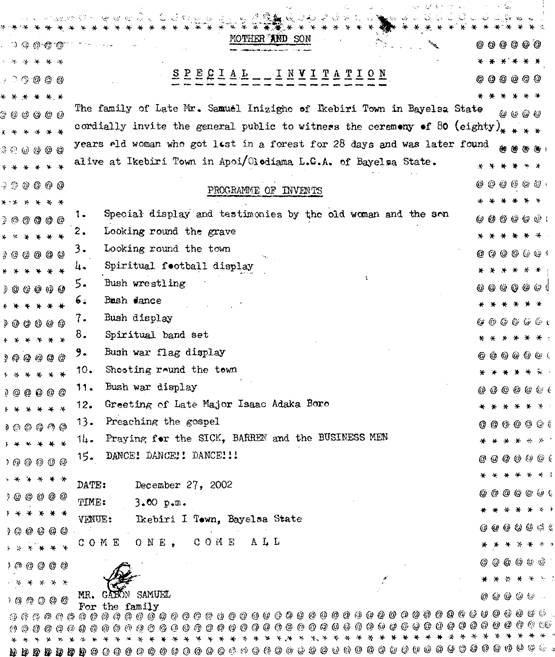

So we were delighted to

receive the following invitation from Samuel Gabon to visit Ikebiri,

to attend the following rather unusual proceedings and talk to Richard’s

family.

We made out way by car to Yenagoa, in

After a couple of hours, we

turned off into a side-channel and reached calmer waters, where not all the

trees had been taken out and the occasional bird ventured to the waterside.

There were no other power-boats and the whole region was more like the Delta I

remembered from earlier trips, a tranquil if humid place. We eventually reached

Ikebiri, our whole bodies buzzing with the vibration

of the outboard, and tied up at the main jetty which was sloping into the water

in an alarming way. The village is a long thin strip of wooden and cement

houses along the edge of the water, which is lined with canoes and fish-traps.

These settlements are very cut off, no water, electricity or telephones and

unless you have a fast boat, very remote from services such as clinics. There

are few tiny shops selling washing-powder, tomato paste and Robb vapour rub,

those commodities without which Nigerian life could not go forward.

As it turned out, there was

some dispute about the festival and part of the village told us they

disapproved and would not be attending. As the start was delayed, we made a

visit to Richard’s grave (a cement slab next to his family house) and saw the

actual building that Kay had lent money to build, so different from the one in

the photographs.

The festival itself was a

curiosity. Its author had set up a large framework covered in cloth, and hung

on it a hugely miscellaneous variety of objects including plastic machine guns,

cloths and other items. In front of it was desk, sporting a disconnected

telephone which the Master of Ceremonies consulted at regular intervals. The

old woman did not appear to tell her story and Late Major Isaac Boro did not greet us. The performers were in fact

schoolboys motivated by the chance to dress up and march around,

playing ‘bush football’ and dancing in lines, marshalled by Samuel Gabon like

an old style scoutmaster. It was hard to link the items on the programme with

what we saw, and in the event

we were thankful that ‘shooting round the town’ did not take

place. In the event, a crowd drifted up drawn by the strange spectacle of two

white people taking seriously what appeared to them as the slightly mad

activities of someone marginal to the

community.

Watching the sky darken and

thinking of the ride back, I urged Kay to leave but her sense of politeness

meant that we stayed until the dancing was announced. Suddenly, everyone

thought that it was now time to greet us seriously and as we went back to the

boat, we were stopped and engaged with the usual pleasantries. Further delays

meant that when we finally set off the night met us about an hour from Yenagoa. These boats have no lights, and yet they continue

to ply the main channel. This meant that you had to judge the direction and

path of other boats by ear until they were really close; the whole experience

reminded me of being on a pier-end driving machine with no second chances if

you run off the road. Kay, of course, was completely unfazed, sitting in the

centre of the boat, having higher thoughts about Ijọ sentence structure. We made it safely back with a

due sense of fitness as having finally made the visit to the grave; but with my

feeling that I would rather go hang-gliding off Everest than experience this

again.

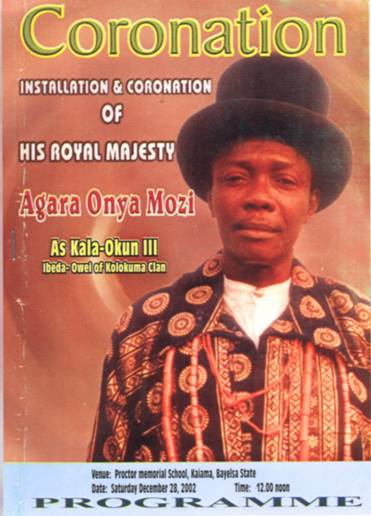

This was a visit to a place

she had never been, but Kay’s ‘own’ village was Kaiama,

about an hour’s drive east of Port Harcourt, and she had built a house there

with a plan to retire and pursue a Confucian life of disinterested scholarship.

I always thought this was unlikely to happen, because she was too attached to

the buzz of life on the campus. But Kaiama was always

entertaining to visit, no more so than when we attended the coronation of the

King of the Kolokuma people, Kala-Okun

III, a post which has gradually been growing in splendour.

Tony Blair and his

imperceptive cohorts are always trying to ‘modernise’ the monarchy, complaining

of the tedious rituals and the strange clothes worn by Black Rod or Her

Majesty. But Nigerians are astute watchers of these ceremonies and find much to

imitate and indeed expand upon. Apart from the obligatory cultural dancing and

lengthy speeches, the key events were the attendance of the many sub-chiefs and

reverends or self-appointed bishops of unusual churches. The bowler hat is the

most-favoured headgear in this region, although trilbies and toppers are also

popular. But the dull colours Europeans use hardly appeal, so the hats are

often spiced up with glitter or picked out in green and red. Bishops in

particular have a licence to design their own robes and crosiers and their

creations would put Giovanni Versace to shame, rippling in gold and silver. The

women wear enormous head-ties, gold and red, whirling up on their heads like

cones of Italian ice-cream. As Kay was a long-term resident of the village we

were placed on the stage, behind the throne, which was a three-times

normal size chair. It was as if we were trapped in those old films where the

humans shrink and wander amazed among gigantic furniture. We sipped fruit

champagne and gazed as old women came with sacks of banknotes and threw them at

the future king, uttering shrill cries of praise.

I was only an occasional

visitor to the Delta, but Kay lived in multi-coloured world all the time. I am

sorry I’ll no longer have the window on this very different world that she

inhabited.